A familiar pattern, in an unexpected place

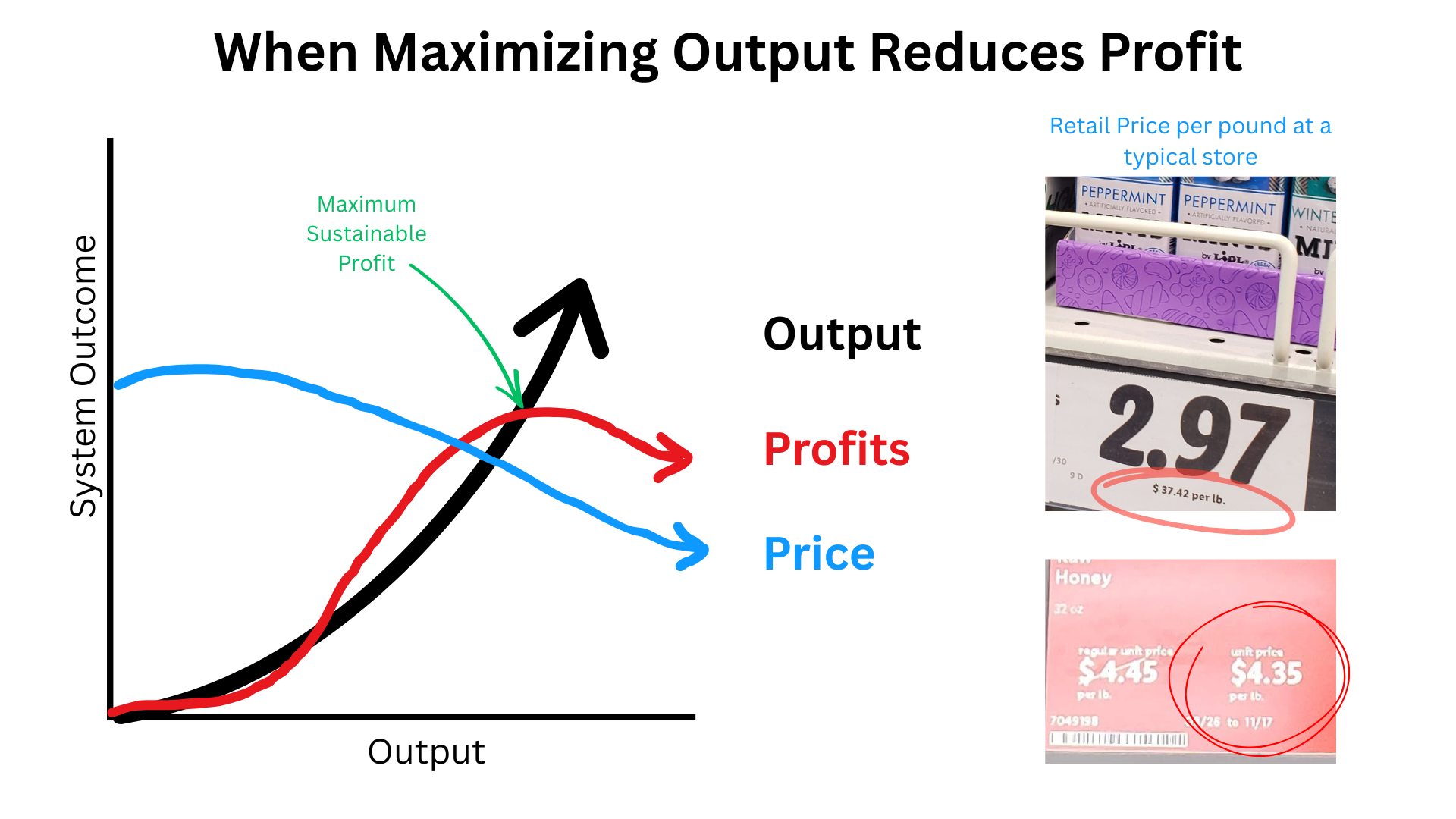

Across business, operations, and economics, there is a recurring failure mode: when organizations fixate on maximizing a single output metric, overall performance often deteriorates rather than improves.

If you’ve followed my writing on BAFO (Best and Final Offer) dynamics, you already recognize the pattern:

- Optimize narrowly for the visible metric

- Strip away slack, buffers, and redundancy

- Declare success when short‑term numbers improve

- Ignore downstream fragility until the system breaks

Most people associate this pattern with corporate procurement, financial engineering, or supply‑chain squeeze tactics.

But the same logic has quietly migrated into a place few expect:

Industrial beekeeping.

This is not a metaphor stretch. It is a structurally identical incentive failure.

The BAFO mindset, applied to living systems

This pattern was first explored directly in a corporate and negotiation context in BAFO-style optimization, where short-term leverage is prioritized over long-term system health.

BAFO thinking treats relationships as transactional and adversarial:

- Maximum extraction, minimum concession

- Short evaluation windows

- Replace partners instead of maintaining resilience

- Externalize long‑term costs

In corporations, this looks like:

- Supplier margin compression

- Labor burnout

- Deferred maintenance

- Financial engineering replacing operational health

In beekeeping, the same logic appears as:

- Maximum honey extraction

- Migratory stress across thousands of miles

- Artificial feeding to replace biological outputs

- Colony replacement instead of colony stability

The metric changes.

The logic does not.

Incentive collapse: when optimization eats its own foundation

In business scholarship, this failure mode is well understood.

When organizations optimize narrowly for a single visible metric, they often destroy the conditions that made that metric achievable in the first place. Strategy literature distinguishes between value creation and value extraction — and warns that over‑optimizing the latter degrades the former.

This is why practices that look successful on paper eventually underperform:

- Supplier relationships hollow out

- Operational slack disappears

- Fragility replaces resilience

The same dynamic applies in biological systems.

Short‑term optimization works — until it doesn’t.

In business, we see it when:

- Supply chains snap under stress

- Institutional knowledge disappears

- Firms become brittle instead of efficient

In beekeeping, we see it when:

- Colonies weaken despite higher inputs

- Disease pressure rises

- Pollination reliability declines

- Colony loss becomes normalized

At that point, the response is familiar:

“This is just the cost of doing business.”

That sentence marks the moment value destruction is reclassified as an operating expense.

Why bees expose the flaw more clearly than balance sheets

Biological systems are less forgiving than spreadsheets.

You can defer maintenance on a factory.

You can refinance debt.

You can reclassify losses.

You cannot indefinitely extract biological labor without consequences.

Bees do not negotiate.

They do not accept narrative framing.

They respond only to conditions.

When conditions cross a threshold, they adapt — or withdraw.

This makes beekeeping a uniquely clear mirror of systemic failure:

- There is no accounting trick for ecological debt

- There is no PR strategy for weakened colonies

- There is no bailout for broken pollination networks

From BAFO to biology: the same failure across domains

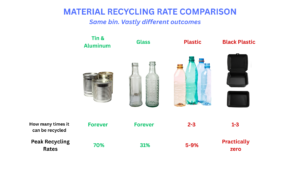

This pattern is not unique to bees or procurement.

It appears wherever decision‑makers are insulated from the long‑term costs of their optimization choices.

In negotiation and sourcing, BAFO‑style tactics often maximize short‑term margin while quietly eroding supplier reliability, innovation, and trust.

In operations and strategy, this is the classic error of optimizing a subsystem at the expense of the whole — a well‑documented source of systemic failure.

Biology simply exposes the flaw faster.

Living systems cannot refinance damage, defer maintenance indefinitely, or reclassify losses. When extraction exceeds regeneration, performance declines — regardless of intent.

Bees make visible what organizations often obscure:

- Throughput is not health

- Extraction is not productivity

- Replacement is not resilience

Once this distinction becomes clear, the same logic is impossible to ignore elsewhere.

The reason this matters is not sentimental.

It is diagnostic.

Bees reveal what BAFO‑style optimization does everywhere:

- It mistakes throughput for health

- It mistakes extraction for productivity

- It mistakes replacement for resilience

Once you see this pattern in biology, it becomes impossible to unsee it in organizations, markets, and policy.

Outcomes are not limited to human organizations

If we apply the same incentive structures described above to biological systems, we observe the same outcomes seen in human organizations.

A detailed case study examining these dynamics in beekeeping is documented in the Colony Collapse / Absconding Colony Hypothesis (ACH), which analyzes how excessive honey production expectations, and short‑term yield optimization correlate with declining colony stability over time.

→ Colony Collapse / Absconding Colony Hypothesis (ACH)

When optimization ignores what sustains a system, maximization shifts into abuse — whether intentional or not — and the conditions that made success possible begin to erode.

— 1Gaea