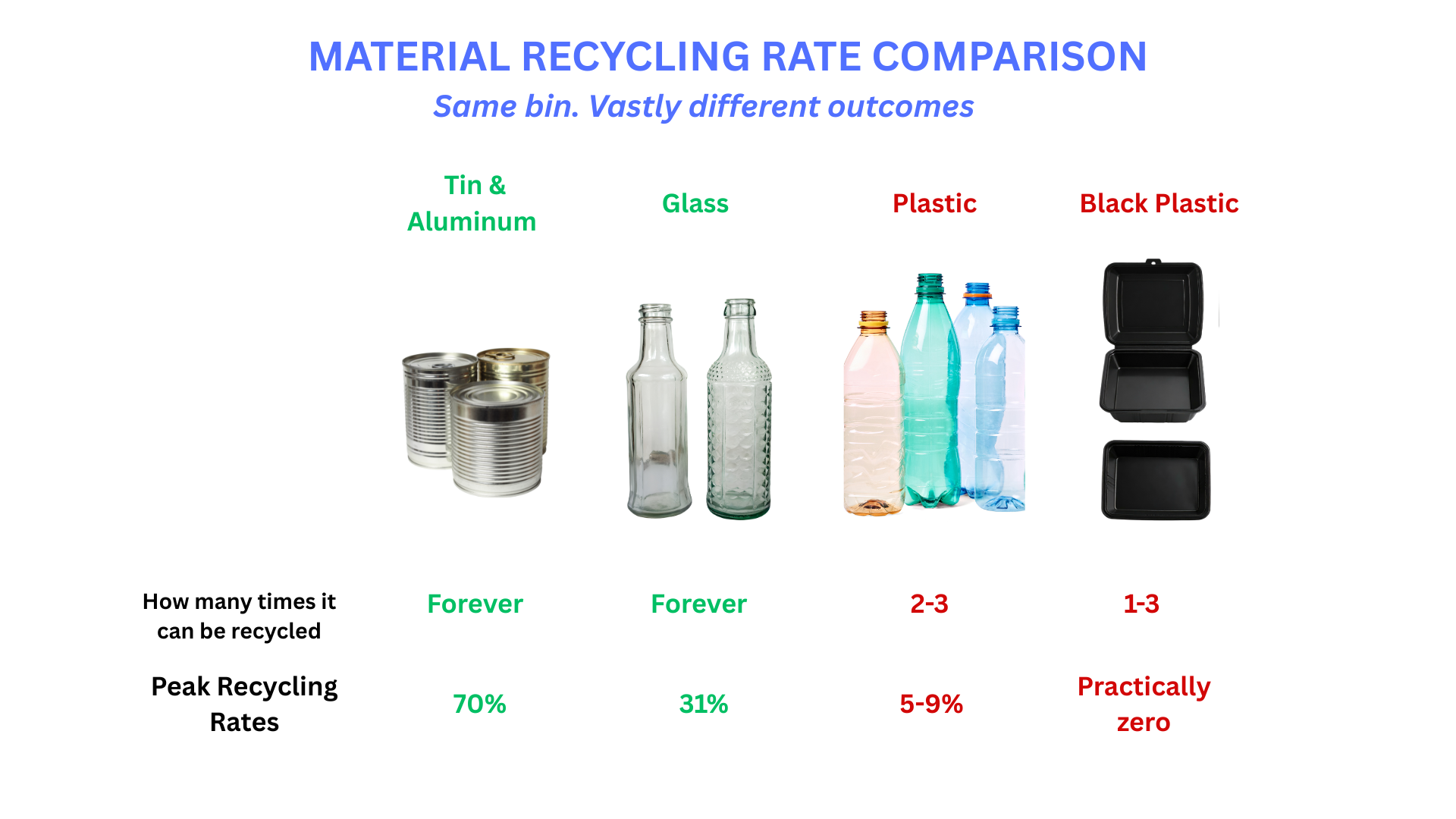

Black Plastic, One Poster Child for Our Greenwashing Epidemic

The Problem

Most plastic drink bottles are made from PET, a plastic that has real recycling value only if it stays clear. That clarity determines whether the material can be reused or whether it drops into a lower‑value path.

Bottle caps are different. They are usually made from polypropylene (PP), not PET. This is intentional and good design. Using a different plastic protects the PET bottle stream from contamination and allows the two materials to be separated later.

So the problem is not that caps contaminate bottles.

The problem is what happens to caps — and other small plastic packaging — after separation, once they enter the real recycling system.

What Actually Happens to Caps

Because caps are produced in many different colors, once they are collected and processed together they immediately form a mixed‑color PP stream. A mixed‑color stream cannot realistically be turned into high‑quality plastic — much like mixing many different paint colors inevitably produces a muddy brown, no matter how bright the originals were.

As a result, this material is almost always downcycled — turned into a lower‑quality product that cannot be recycled again — often into black plastic items, such as restaurant takeout containers.

At this point, the plastic’s future is no longer determined by chemistry, but by how recycling systems actually work.

An Important Clarification

Black polypropylene is not unrecyclable by nature.

If black PP were collected separately, kept clean, and known with certainty to be polypropylene, it could be washed, melted, and remolded. This already happens in controlled industrial settings, such as factory scrap and automotive manufacturing.

But municipal recycling does not operate under controlled conditions.

Why Black Plastic Fails in the Real World

Most municipal recycling facilities rely on optical sorting systems that use near‑infrared (NIR) light to identify plastics by type.

Black plastic is usually colored with carbon black pigment, which absorbs that light. To the sorting system, the plastic is effectively invisible.

When the system cannot reliably identify a plastic:

- It cannot sort it by material

- It cannot guarantee purity

- It cannot sell it with confidence

So the plastic is rejected — not because it cannot be recycled, but because the system cannot see it.

This is a systems failure, not a materials failure.

How a Technical Possibility Became a Practical Dead End

Black plastic works upstream because it is cheap, looks clean, and hides variability in recycled feedstock.

Downstream, it fails because recycling systems are designed for speed, scale, and certainty — not exceptions.

The result is a quiet but predictable outcome:

- The PET bottle is protected

- The PP cap is separated

- The PP is downcycled into black

- The black plastic exits the system after one use

That is not circularity. It is delayed disposal.

The Core Insight

The problem is not that black plastic cannot be recycled.

The problem is that we design massive volumes of plastic that can only be recycled if everything works perfectly, while knowing the system does not.

Design decisions made upstream quietly determine whether plastic has a future — or a single last use.

A Practical Design Rule

Stop using plastic colors that recycling systems cannot reliably identify.

That means:

- Avoid carbon-black plastic for disposable food packaging

- Use scanner-detectable pigments when dark colors are required

- Limit unnecessary color variation in high-volume plastic items like caps

- Reserve true black plastic for durable, long-life products, where one-time disposal is not the default outcome

These steps do not require new laws or perfect recycling behavior. They simply stop failure from being built in at the design stage.

Concrete Proposals (Testable, Not Theoretical)

These proposals can be tested with existing materials, equipment, and supply chains. No new consumer behavior or municipal overhaul is required.

- Pilot mottled or speckled PP food containers

Use mixed-color polypropylene from cap streams to produce mottled containers that remain visible to optical sorters. Measure acceptance, durability, and resale value compared to carbon-black containers. - Require NIR-detectable pigments for any black packaging

Where black aesthetics are non-negotiable, mandate pigments that can be identified by near-infrared sorting systems already used in MRFs. - Shift disposable packaging to dark, detectable colors

Replace carbon black with colors known to remain detectable, such as navy, dark green, brown, or burgundy, and compare downstream capture rates. - Limit true carbon-black plastic to long-life products

If carbon black must be used, restrict it to durable goods with multi-year service lives rather than single-use food packaging. - End green marketing claims for plastics without a second life

If a product has no realistic path through existing recycling systems, it should not be marketed as recyclable or eco-friendly. - Reuse Your black Plastic containers

Since black plastic is not LIKELY to be recycled, a more eco conscious choice is to reuse for storage (whether it is for food or something else) - Help spread the truth

Consider asking your restaurant to change to from black plastic or any plastic (but particularly black) to aluminum for their takeout containers. Unfortunately, your restaurant may not even be aware that black plastic doesn’t not get recycled. Even their supplier may not be aware of it but sell it as eco-friendly and low cost. Aluminum is a far better alternative because it can be recycled if clean. If not recycled, it will break down over time, and does not shed micro plastics.

The Bottom Line

Black polypropylene can be recycled — in theory.

But under today’s municipal recycling systems, it usually isn’t.

Until design choices reflect how recycling actually works — not how we wish it worked — small packaging decisions will continue to lock plastic into one‑way paths.

Design that fails to take into account the recycling process so downcycling is the only option is a failed system . To promote this as eco friendly is greenwashing because the inevitable result is just delayed disposal to a landfill. Hardly a circular system.

And once that happens, no bin, label, or good intention can undo it.